This situation painfully demonstrated how vulnerable our modern monetary and economic system is. But we also owe this crisis an invention that will change our world. A man or a group called Satoshi Nakamoto – who hides behind this pseudonym is unknown still today – invented the Blockchain. „So far,“ says a white paper published by Nakamoto on the Internet, „global trade is almost entirely based on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. The crisis has clearly shown that these financial institutions are not „third parties to be trusted“.

The idea Nakamoto had against this background is basically simple: we need a technical system that allows money to be transmitted directly from the sender to the recipient. This is intended to eliminate banks that traditionally carry out such transactions. Blockchain is the technique that enables such an immediate transfer, Bitcoin is the currency that can be transferred. As simple as the idea may be, its technical realization is just as complex. Because it is indispensable for the success of Blockchain that the money, more precisely: the data that represent the money, flows safely from one party to another.

Nakamoto’s innovation thus responds to a crisis that has many symptoms and extends far beyond the financial sector. Its core is a loss of confidence that extends not only to the financial world, but to large parts of public life and is expressed in the accusation of the „lying press“ as well as in the concept of the „postfactual age“, which has been so much talked about since Donald Trump’s election. The Americanist Michael Butter rightly describes the many circulating conspiracy theories as a „symptom of a deeper crisis of democratic societies“, which in his opinion „cannot cope with the pressing problems of the 21st century“ when they „can no longer agree on what is true“. All these phenomena are interrelated and can be bundled under the banner of the „epistemic crisis“. The old philosophical question „What is truth?“ remains unanswered, and so confidence in the media as well as in state institutions is waning. Blockchain is a reflex to this situation. It aims to build trust by technologically answering the question of what data is reliable and can be considered true through encryption and decentralization.

Truth and currency in Faust

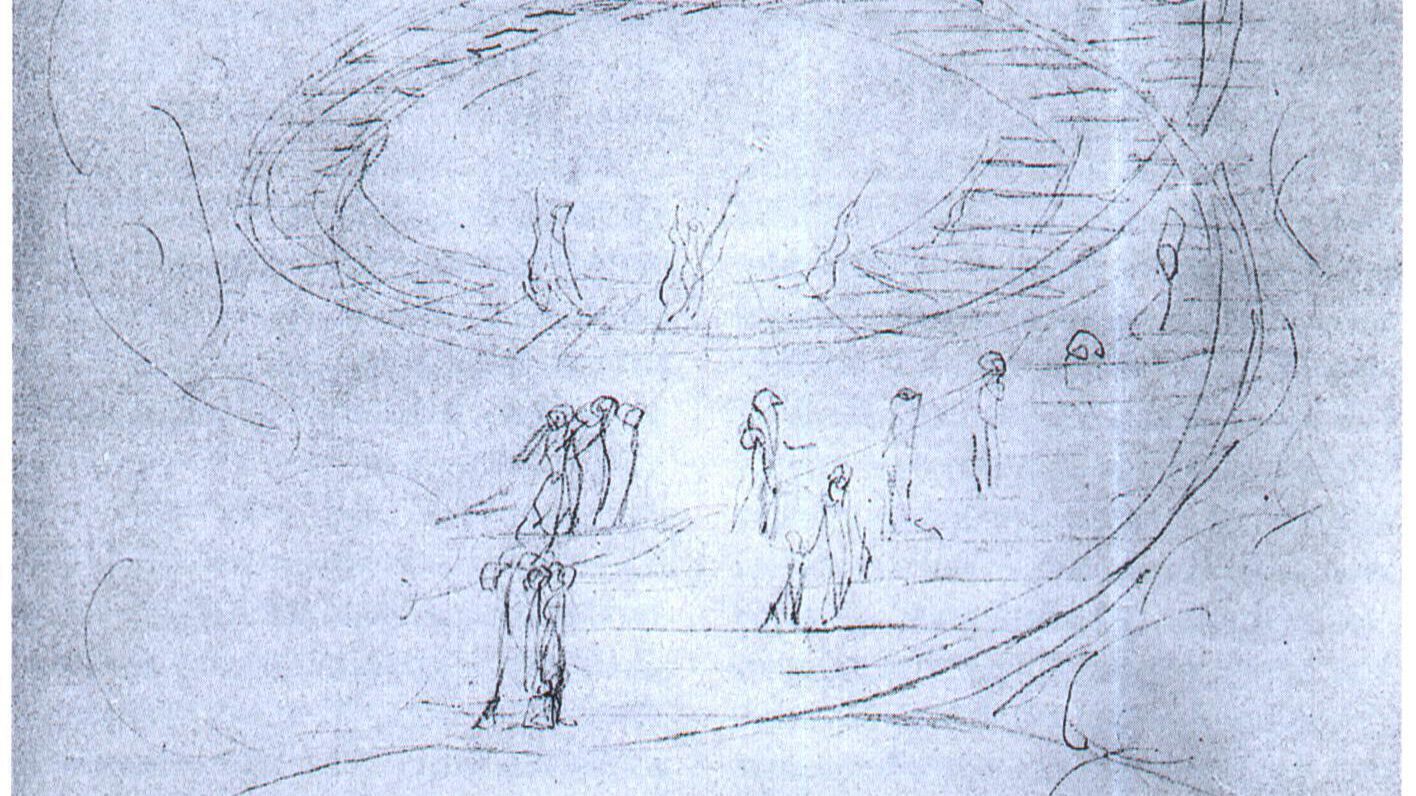

As big as the differences between Bitcoin and other traditional currencies may be – this crypto currency has its origin in a crisis situation in common with many types of money. In the second part of his tragedy “Faust”, Goethe made the connection between crisis and currency the subject. What is shown there in the first act published in advance in 1828 reads like an anticipation of current events. This allegory of „Faust“ scenes is connected with the concept of truth that Goethe lets shine through in his poetry.

Of course, „so bar, so bare as if / The truth was coin“ it does not appear Faust. Just as Lessing’s Nathan dresses his truth about religion in a „fairy tale,“ Faust shows the truth in a picture of nature, namely in the rainbow. It allows indirect access to the light that cannot be viewed directly. For Goethe, the colors of the rainbow are „deeds of light“, and just as a person’s actions allow conclusions about his character, so the colors allow conclusions about light itself as „deeds“ of light. Faust’s monologue at the beginning of the plot is reminiscent of an essay by Goethe on the „Theory of Weather“ from 1825, which states: „The true is identical to the divine, can never be directly recognized by us, we only see it in the reflection, in the example, symbol“. Thus, as the Chorus mysticus proclaims at the end of Faust II, „all that is transient“ is simply „only a parable“, all reality is only a clouded mediation, a „colorful reflection“ of truth. All the regions of the world through which Faust is guided according to this quasi epistemological preamble stand for certain themes, and the colorful imperial court scene at the beginning of the drama shows the complex connection between truth, crisis and currency in a light that is still capable of illuminating events today.

In the „Throne Room“ of the “Emperor’s castle”, the deep crisis of a state and its (questionable) remedy by Mephisto, who invents a new currency, becomes apparent.

A „world of error“ has „unfolded“ there. It „rages feverishly in the state“: the rulers of the court live in rush and breeze, the emperor would rather „break free“ from „worries“ and „just enjoy“, when egoism, fraud, corruption and bribery have brought about unsustainable conditions. The government has lost the trust of the people and thus its authority. The state has become ungovernable.

In this situation, Mephisto, who plays the role of court jester, is supposed to help the emperor with good advice. His diagnosis is as simple as it is valid: „In this world, what isn’t lacking, somewhere, though? / Sometimes it’s this, or that: here what’s missing’s gold.”

To remedy this embarrassing situation, Mephisto proposes that the treasures buried in the soil of the empire be raised. There lies what men would have buried since the Romans and into the present day in times of need, and with the clever turn: „All this lies quietly buried in the ground, / The ground is the emperor’s, he shall have it,“ Mephisto hands over these goods to the ruler. But how are the treasures hidden deep in the earth to be raised? That doesn’t have to happen! Mephisto invents paper money, which the hypothetical treasures in the imperial ground are intended to cover.

Goethe knew that currency was based on trust. The Jenaer Allgemeine Literaturzeitung, which was one of his favorite readings, regularly published articles on financial policy topics. „Every piece of paper money,“ says one of these essays, „has value only because there is certainty that it can be realized at a future point in time.

This is exactly what the treasurer of the imperial palace heeds:

„See and hear the scroll, heavy with destiny,

That’s changed to happiness, our misery.

‘To whom it concerns, may you all know,

This paper’s worth a thousand crowns, or so.

As a secure pledge, it will underwrite,

All buried treasure, our Emperor’s right.

Now, as soon as the treasure’s excavated,

It’s taken care of, and well compensated.“

The emperor is surprised that people recognize printed paper as a means of payment, but Faust convinces the ruler that „spirits, worthy to look deeply / could have unlimited confidence in the boundless“.

The new currency is the result of a deep state crisis, which is reflected not least in the lack of confidence of the population in the old authorities. The new money works because the people trust that it is covered by mineral resources. It is based on a truth believed. First of all, the fresh money has a tremendously invigorating effect. „First we made him rich,“ says Mephisto to Faust about the Emperor, „now we shall amuse him.“ To this end, Faust presents the figures of Helena and Paris in a kind of cinema performance before the eyes of the banished court. Finally, he no longer knows how to separate appearance and existence. He falls in love with Helena, wants to reach out for her and thus brings the apparatus that evokes the imagination to exposition. The big bang with which the first act ends may at least give an idea of the future of this state. The „paper ghost of the guilders“ (Mephisto) is ultimately little more than an illusion at the imperial court and will therefore end little else than the illusion of the conjured Helen.

Goethe himself was skeptical about paper money, and for good reason: both in France and Austria there was devastating inflation after its introduction, as the currencies were not covered by real values. Goethe knew the dangers associated with the issuance of paper money. He lets his fool draw the right conclusions in „Faust“. This „two-legged tube“ overslept the introduction of the new currency in intoxication and can therefore hardly believe that the „magic sheets“ that the emperor gives him are „worth the money“. So he decides to turn the new illusory wealth into „real estate“. Mephisto says, „Who else doubts our fool’s joke?“ Some other new rich people act less wisely, who, despite „all the treasures, Flor“ always remain „still“ and amusingly drink and gamble away the new prosperity. „If they had the Philosopher’s Stone,“ Mephisto comments on their behavior, „the wise man lacked the Stone.“ With this he alludes to the lapis philosophorum, which in the Middle Ages was intended to turn common metal into precious gold.

Computing power becomes money

Did Nakamoto find this legendary Philosopher’s Stone? Money is created at Blockchain by turning computing power into money. „Mining“ is the name given to this process with a term reminiscent of mining gold underground. All information that the users of the blockchain have entered in a register is converted into a hash value with the help of a formula. Of course no person would undergo the extremely energy-intensive effort of this conversion of register entries, if one could not expect something in return. That’s why Nakamoto invented the Bitcoin as a reward. Of course, Nakamoto saw the danger that the new currency would run the risk of drastic inflation if the stock of virtual coins to be stripped were not limited. So he set the amount of bitcoins at 21 million. Currently, anyone who works successfully in mining will receive 12 bitcoins as a reward. Similar to mining, the efforts involved in mining are becoming ever greater: every four years, the reward for the miners is reduced by half. According to this, the entire stock of bitcoins should be depleted by 2140.

Bitcoin is just one example of a crypto currency, of which there are now countless. In February 2018, for example, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro introduced the crypto currency Petro, taking hundreds of millions of dollars on the very first day. The owners of Petro have no legal claim to the redemption of this currency. It is based solely on investor confidence. A natural resource, oil, is supposed to provide security as cover. One might almost believe that Maduro had read Goethe’s „Faust“, but his idea to use a new currency to restructure the highly indebted state, which is hardly capable of taking action because of corruption and mismanagement, is so reminiscent of the events in the imperial palace.

Whether these crypto currencies will have a better future than the „magic sheets“ that Mephisto created remains to be seen. No one can predict whether Bitcoin will return to similar highs after heavy losses in last winter or whether the hype surrounding the new currencies will end like the first act in „Faust“: With a big bang.

But even if Bitcoin and other crypto currencies should share the fate of Mephistophelian paper money and disappear again, the underlying idea of a secure and direct transfer of data, which does not depend on intermediaries, will continue to exist and find new applications. Paper money has also established itself through adjustments and changes, although the early attempts made in France and Austria, for example, have failed dramatically. Blockchain technology will prevail if it is able to be so secure that the population trusts it more than the discredited traditional economic institutions and states. It should therefore contribute, at least in economic terms, to resolving the epistemic crisis.

Der Orginaltext dieses Artikels erschien auf Deutsch in der NZZ am 14.03.2018 unter dem Titel „Was Nicolàs Maduro aus Goethes «Faust» lernte“

https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/goethes-mephisto-erfand-die-kryptowaehrung-ld.1365281